Hoping Stephan Kinsella or Hans-Hermann Hoppe won’t sue me for copyright violation, I can think of no better way for this site to memorialize this milestone than to reproduce this cornucopia of resources from The Property and Freedom Society, whose site I could not safely open. Since maybe you can’t either, I’m grateful to internet argonaut Dave Lull for copying and pasting its table of contents into an email. (Two humble contributions of mine made the list!)

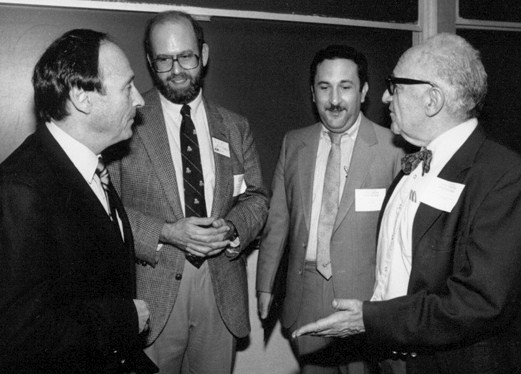

Murray was a lad of 58, I a mere babe in the libertarian woods (only 29), when I first met him. What a powerful, creatively synthesizing mind; what a generous friend! May God grant him eternal life in the Kingdom!

Anthony Flood

Rothbard at 100: A Tribute and Assessment

– Other PFS books –

Rothbard at 100: A Tribute and Assessment, Stephan Kinsella and Hans-Hermann Hoppe, eds. (Papinian Press and The Saif House, 2026).

Rothbard at 100: A Tribute and Assessment, Stephan Kinsella and Hans-Hermann Hoppe, eds. (Papinian Press and The Saif House, 2026).

Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995) was one of the world’s greatest champions of the human liberty. In his honor, and to commemorate his 100th birthday, on March 2, 2026, the Property and Freedom Society (PFS) has assembled this collection of tributes to and commentary on him and his work by PFS members, including many who knew him personally.

This book is released in digital form today, March 2, 2026, on Murray’s 100th birthday. Print, in both paperback and deluxe hardcover, and kindle/epub/pdf versions will be made available shortly.

[Note: the links below will go live March 2, 2026, at 12:01am CST, as will this announcement: Rothbard at 100: A Tribute and Assessment Published Today]

Contents

Front Matter

Part 1*

-

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, “Coming of Age with Murray”

- Jeffrey F. Barr, “The Last Lecture”

- Thomas J. DiLorenzo, “The Inspiring and Courageous Intellect of Murray Rothbard”

- Douglas E. French, “Remembering Murray Rothbard: Teacher, Friend, and Inspiration”

- Jörg Guido Hülsmann, “Three Channels of Asset Inflation”

- Lee Iglody, “The Man Across the Hall: My Time with Professor Rothbard”

- Thomas Jacob, “Murray Rothbard, Mises University 1990, and the Power of Living Institutions”

- Stephan Kinsella, “Mises, Rothbard, Hoppe: An Indispensable Framework”

- Jeffrey A. Tucker, “The Murray Rothbard I Knew”

Part 2

-

- Saifedean Ammous, “Murray Rothbard: An Ode to an Intellectual Hero”

- Juan F. Carpio, “Murray Rothbard, Statelessness, and the Kritarchy: Five Millennia of Evidence for Competitive Lawmaking”

- Fernando Fiori Chiocca, “The First Knight of Libertarianism”

- Jeff Deist, “Appreciating Rothbard’s Political Genius”

- David Dürr, “Encountering Rothbard: Property Rights as the Key to Anarchy”

- Alessandro Fusillo, “Rothbard, Philosopher of Law”

- Sean Gabb, “Rothbard: An Appreciation from England”

- David Howden, “Privatizing Entry, Dissolving State Borders: Immigration Policy as the Apex of Rothbardian Libertarianism”

- Thorsten Polleit, “Thank you, Murray Rothbard, For Your Extreme ‘Defense of Extreme Apriorism’”

- Josef Šíma, “Life in a World Without the Rothbardian One Big Liberty Master Button”

- Rahim Taghizadegan, “Murray N. Rothbard and the Demystification of Economics”

Appendix

*Part 1 consists of PFS authors who personally knew or met Rothbard

Related

Biographical

-

- Wikipedia

- Mises Institute bio

- Rothbard.it bibliography

- Rothbard, Young Murray Rothbard: An Autobiography

- Rothbard, “What’s Wrong with the Liberty Poll; or, How I Became a Libertarian,” Liberty (July, 1998), p. 52

- Rothbard, The Essential Rothbard, David Gordon, ed. (2007)

- Rothbard, The Betrayal of the American Right (2007)

- Gerard Casey, Murray Rothbard (Continuum, 2010)

- Roberta Modugno, The Legacy of Murray N. Rothbard: Libertarian and Austrian Economist (Springer Nature, 2025)

- Justin Raimondo, Enemy of the State: The Life of Murray N. Rothbard (2000)

- ——, Reclaiming the American Right: The Lost Legacy of the Conservative Movement (2008)

- Brian Doherty, Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement (2008)

- ——, Modern Libertarianism: A Brief History of Classical Liberalism in the United States (2025)

- Joseph T. Salerno and Patrick Newman, Murray N. Rothbard: The Making of an Austrian Economist (Mises Institute, forthcoming)

Bibliographical

-

- Rothbard Bibliography

- David Gordon, “Murray N. Rothbard: Chronological Bibliography (1949–1995),” in Rothbard, The Essential Rothbard, David Gordon, ed. (2007)

- Rothbard Books

- A Guide to Reading Murray Rothbard

- David Gordon, Murray N. Rothbard, linking to Rothbard books, articles, and media

- Online Library of Liberty: Rothbard

- Murray N. Rothbard, Rothbard A to Z, compiled by Edward W. Fuller, edited by David Gordon (Auburn, Ala.: Mises Institute, 2018)

Correspondence

-

- Rothbard, “Rothbard’s Confidential Memorandum to the Volker Fund, ‘What Is To Be Done?’,” Libertarian Papers 1, 3 (2009)

- Rothbard, Murray N. Rothbard vs. The Philosophers: Unpublished Writings on Hayek, Mises, Strauss, and Polanyi, Roberta A. Modugno, ed. (2009)

- Rothbard, Strictly Confidential: The Private Volker Fund Memos of Murray N. Rothbard, David Gordon, ed. (2010)

- Joseph T. Salerno, “Rothbard: These Are the Best Libertarian Educators,” Mises Wire (05/24/2017) (Rothbard, letter to F.A. “Baldy” Harper (July 9, 1961)

- Daniel J. Flynn, “Letters to Frank Meyer Reveal Rothbard’s Views on Lincoln, Slavery, and Popular Sovereignty,” Mises Wire (10/07/2025)

- ——, “Rothbard, Populism, and the Elites,” Mises Wire (10/14/2025) (re memo to Frank Meyer, September 12, 1955)

- ——, “New Rothbard Letters Show His Early Opposition to both Nixon and Reagan,”Mises Wire (10/22/2025)

- ——, “New Rothbard Letters Show He Rejected both Drug Abuse and the Drug War,” Mises Wire (10/27/2025)

- ——, “Murray Rothbard’s Lost Letters on Ayn Rand,” J. Libertarian Stud. 29, no. 2 (2025): 35–50

- Rothbard, “Mises and Rothbard Letters to Ayn Rand,” J. Libertarian Stud. 21, no. 4 (Winter 2007): 11–16

- Rothbard, The Essential Rothbard, David Gordon, ed. (2007)

Tributes/obituaries/memories/

-

- Murray N. Rothbard: In Memoriam (Auburn, Ala.: Mises Institute, 1995) (various authors)

- JoAnn Rothbard, “My View of Murray Rothbard” (March 1, 1986), delivered at the Mises Institute’s celebration in honor of Murray Rothbard’s sixtieth birthday, included in JoAnn’s obituary, “JoAnn Beatrice Schumacher Rothbard (1928-1999),” Mises Daily (Oct. 30, 1999)

- “Rothbard Remembered,” Liberty (March, 1995): 20–26 (various authors)

- Douglas E. French, “Rothbard the teacher,” Liberty (May 1995), p. 14 & 69

- Carl Oglesby, “Rothbard the isolationist,” Liberty (May 1995), p. 14

- Hoppe, Murray Rothbard, R.I.P., The Free Market 13, no. 3 (March 1995)

- Harry C. Veryser, “Murray Rothbard: In Memoriam,” The Intercollegiate Review 31, no. 1 (Fall 1995): 41

- William F. Buckley Jr., Murray Rothbard, RIP, National Review (Feb. 6, 1995)

- Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., William F. Buckley, Jr., RIP, LewRockwell.com (Feb. 27, 2008)

- ——, Murray Rothbard Soars, Bill Buckley Evaporates, LewRockwell.com (

March 29, 2016) - David Gordon, A Birthday Tribute to William F. Buckley, Jr., LewRockwell.com (Nov. 17, 2005)

- Thomas Fleming, Murray Rothbard, R.I.P., Chronicles (April 1995)

- Man, Economy, and Liberty: Essays in Honor of Murray N. Rothbard, Walter Block and Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., eds. (Mises Institute, 1988)1

- Hoppe, Interview with Hans-Hermann Hoppe, an Anti-Intellectual Intellectual (Syahdan, 2008) and others in Hoppe Biography

- R.W. Bradford, “At Liberty,” Liberty (September, 1997), p. 21, pp. 25–262

- Wendy McElroy, Murray N. Rothbard: Mr. Libertarian, LewRockwell.com (

July 6, 2000) - Ron Paul, End the Fed (2009), comments on Rothbard3

- Sheldon Richman, Murray Rothbard, FEE.org (March 24, 2010)

- Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., “Rothbard’s Legacy,” Mises Daily (June 8, 2010)

- J Richard Duke, “In Defense of Murray Rothbard’s Legacy,” Biblical Truths and Austrian Economics (Substack Jan 16, 2026)4

- Hoppe Awarded the Murray N. Rothbard Medal of Freedom (2015)

- Hoppe, “Coming of Age with Murray” (Mises Institute 2017) (youtube)

- Matt Zwolinski, Seven Cheers for Murray Rothbard, Bleeding Heart Libertarians (Oct. 28, 2013)

- PFP129 | Memories: Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995) as Mentor and Teacher, Hoppe, DiLorenzo, French, Iglody (PFS 2015)

- John Ganz, “The Forgotten Man: On Murray Rothbard, philosophical harbinger of Trump and the alt-right,” The Baffler (Dec. 15, 2017)

- Jeffrey A. Tucker, Interviewing Author Jeffrey Tucker (April 25, 2018) (starts 10:17)

- Gary North, “Rothbard’s Man, Economy, and State: a Memoir,” Power & Market (04/13/2018)

- David Dürr, “The Inescapability of Law, and of Mises, Rothbard, and Hoppe,” J. Libertarian Stud. 23 (2019): 161–170; text; video

- Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., “Rothbard Was Right,” Mises Daily (July 4, 2019)

- David Gordon, Murray Rothbard RIP, Mises Daily (01/07/2019)

- ——, Remembering Murray Rothbard, Chronicles (Dec. 2019)

- Anthony G. Flood, “The quadrancentennial of Murray Rothbard’s passing” (Jan. 8, 2020)

- Roberta Modugno, “How I Discovered Murray Rothbard,” Mises Wire (03/03/2021)

- PFP252 | Bonus: Murray Rothbard as a Teacher: The UNLV Years—A Panel with Rothbard’s Former Students (AERC2023)

- Anthony G. Flood, “Joe Sobran’s encomia for Murray Rothbard” (March 12, 2025)

- Jeffrey A. Tucker, “Murray N. Rothbard at 100,” Brownstone Journal (March 2, 2026; forthcoming)

Notes

-

- See The Free Market (June 1986), p. 2, listing papers in “Man, Economy, and Liberty: A Conference in Honor of Murray N. Rothbard.” See also: Jeffrey Tucker and Lew Rockwell, “Man, Economy, and Liberty” (17 November 2009) (Tucker interviews Rockwell about Rothbard’s festschrift, published in 1986 in honor of Rothbard’s sixtieth birthday); Rothbard, Man, Economy, and Liberty (1 March 1986) (Rothbard comments and responds to the speakers and papers presented at the “Man, Economy and Liberty” colloquium hosted by the Mises Institute; backup Youtube); Hoppe, Book Review of Walter Block and Llewellyn H.Rockwell, Jr., eds., Man, Economy, and Liberty: Essays in Honor of Murray N. Rothbard, Rev. Austrian Econ. (Vol. 4 Num. 1, 1989). See also Timothy Virkkala, “Bestschrift,” Liberty (Septem

ber, 1989), p. 63. - “I prefer to remember him as the charming, brilliant, and joyous friend he had been in Liberty‘s formative years. He was the wittiest man I have ever met, the best man with whom to spend an evening in a bar that I ever knew. I miss him enormously.”

- excerpted here: “Shortly before Murray [Rothbard] died, I called him to tell him of my plans to run for Congress once again in the 1996 election. He was extremely excited and very encouraging. One thing I am certain of—if Murray could have been with us during the presidential primary in 2008, he would have had a lot to say about it and fun saying it. He would have been very excited. His natural tendency to be optimistic would have been enhanced. He would have loved every minute of it. He would have pushed the “revolution,” especially since he contributed so much to preparing for it. I can just imagine how enthralled he would have been to see college kids burning Federal Reserve notes. He would have led the chant we heard at so many rallies: “End the Fed! End the Fed!”

- Duke is former counsel to the Mises Institute. “Murray N. Rothbard is the most intelligent and informed man I have met in my entire life! He like Ludwig von Mises, refused to speak and write only the truth. This hurt Mises and Rothbard financially their entire lives. They were ridiculed by the mainstream economists, government, new media, academics. But they held to the truth that they knew in their minds and hearts. I knew Murray N. Rothbard personally and he was kind to everyone. He was so brilliant that most people were nervous when they met him. Murray usually told a joke or said something weird, strange, funny or whatever to make people comfortable. He did not laugh; he cackled. He was jovial. I had lunches and dinners with him and spoke with him at the Mises institute. I was the attorney for the Mises Institute in the early years. – JRD”

- See The Free Market (June 1986), p. 2, listing papers in “Man, Economy, and Liberty: A Conference in Honor of Murray N. Rothbard.” See also: Jeffrey Tucker and Lew Rockwell, “Man, Economy, and Liberty” (17 November 2009) (Tucker interviews Rockwell about Rothbard’s festschrift, published in 1986 in honor of Rothbard’s sixtieth birthday); Rothbard, Man, Economy, and Liberty (1 March 1986) (Rothbard comments and responds to the speakers and papers presented at the “Man, Economy and Liberty” colloquium hosted by the Mises Institute; backup Youtube); Hoppe, Book Review of Walter Block and Llewellyn H.Rockwell, Jr., eds., Man, Economy, and Liberty: Essays in Honor of Murray N. Rothbard, Rev. Austrian Econ. (Vol. 4 Num. 1, 1989). See also Timothy Virkkala, “Bestschrift,” Liberty (Septem

That is the title of James Parkes’s patient historical narrative. The subtitle is A History of the Peoples of Palestine. “Palestine,” we have collectively forgotten, names a remnant of the Roman Empire, a remnant that has been occupied by many peoples. He wrote it in the late ’40s, long before “the Palestinian people” was popularized by Yassir Arafat in the ’60s to refer exclusively to its Arab inhabitants, a ruse the world fell for and seems stuck with.

That is the title of James Parkes’s patient historical narrative. The subtitle is A History of the Peoples of Palestine. “Palestine,” we have collectively forgotten, names a remnant of the Roman Empire, a remnant that has been occupied by many peoples. He wrote it in the late ’40s, long before “the Palestinian people” was popularized by Yassir Arafat in the ’60s to refer exclusively to its Arab inhabitants, a ruse the world fell for and seems stuck with.

No one who met Jim Sadowsky could ever forget him. I first saw him at a conference at Claremont University in California in August 1979; his great friend Bill Baumgarth, a political science professor at Fordham, was also there. His distinctive style of conversation at once attracted my attention. He spoke in a very terse way, and he had no patience with nonsense, a category that covered much of what he heard. If you gave him an argument and asked him whether he understood what you meant, he usually answered, “No, I don’t.” He once said to a fellow Jesuit, “that’s false, and you know it’s false.”

No one who met Jim Sadowsky could ever forget him. I first saw him at a conference at Claremont University in California in August 1979; his great friend Bill Baumgarth, a political science professor at Fordham, was also there. His distinctive style of conversation at once attracted my attention. He spoke in a very terse way, and he had no patience with nonsense, a category that covered much of what he heard. If you gave him an argument and asked him whether he understood what you meant, he usually answered, “No, I don’t.” He once said to a fellow Jesuit, “that’s false, and you know it’s false.”

admiration for Thomas is great, but does not inhibit his criticism. Aquinas’s thought on the subject of liberty is, as I shall show in my own way, a mixed bag, but one whose contents every lover of liberty and reason is better off for having explored.

admiration for Thomas is great, but does not inhibit his criticism. Aquinas’s thought on the subject of liberty is, as I shall show in my own way, a mixed bag, but one whose contents every lover of liberty and reason is better off for having explored. I’m taking this opportunity to thank again LCI’s Chief Executive Officer Doug Stuart for interviewing me about

I’m taking this opportunity to thank again LCI’s Chief Executive Officer Doug Stuart for interviewing me about