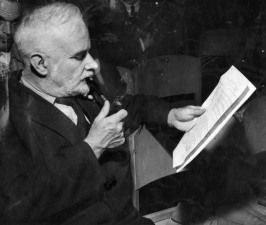

The titles of two books by British philosopher C. E. M. Joad (1891-1953) comprise the title of this post. They resonate with me in ways I will try to describe.

Joad’s life and writings are a recent discovery of mine, too recent for me to have dedicated a portal to his essays on my dormant philosophy site as I had done for many other thinkers. I can’t now recall what occasioned Joad’s coming to my attention. Perhaps he wandered onto the stage of his times about which I’ve been reading lately.

It was his prose style, however, that caught and held my attention, which was then drawn to his biography. I get almost as much pleasure from reading Joad as I do Brand Blanshard, Joad’s contemporary, which is to say, a great deal.

The way Joad wrote has reawakened within me the kind of feelings that led me to philosophy almost fifty years ago. A few years ago I found myself unable to write about it anymore after having proposed a metaphilosophy that drew the criticism of William F. Vallicella, a philosopher I respect. I wrote many pages of notes toward a reply, but found myself unable to articulate to my satisfaction my critique of philosophy’s presuppositions, which critique also serves as an apologetic for orthodox Christian theism.

Perhaps I’ve retreated into metaphilosophy because I despair of reaching philosophical conclusions. Really, what end has my site served other than that of displaying my philosophical interests at the expense of committing to definite answers to philosophical questions?

The charge of conflating defense and critique might occur even to sympathetic readers. Such a charge, however, overlooks a key thesis of the critique, namely, that dependence on God, whether acknowledged, unacknowledged, or even denied, underpins every theoretical enterprise. (Even the enterprise of demonstrating the dependence of all theorizing on God.) An implication of the critique is that denial of such dependence is self-stultifying. Even the failure to acknowledge it is an unstable intellectual position.

As it happened, a little book entitled Return to Philosophy (1935) came into my life, and reading it has encouraged me to give the whole thing another try. Maybe. I’m keenly aware that I had begun to pursue worldview-apologetics and metaphilosophy at the expense of actual philosophizing. Whether I have it in me to philosophize any more is an open question.

For most of his life Joad was not only a socialist, but also a professed atheist who became dissatisfied with the worldview that underpinned that profession. He returned to the Church of England of his youth a few years before his death. (He never repented of his socialism, although he increasingly acknowledged, and feared, that the means to that end was a bloated and rights-violating state.) In The Recovery of Belief (1953) the many arguments he had relied on in support of his atheism pass in review. Some of them are arguments that have occurred to me, as have Joad’s criticisms thereof.

For most of his life Joad was not only a socialist, but also a professed atheist who became dissatisfied with the worldview that underpinned that profession. He returned to the Church of England of his youth a few years before his death. (He never repented of his socialism, although he increasingly acknowledged, and feared, that the means to that end was a bloated and rights-violating state.) In The Recovery of Belief (1953) the many arguments he had relied on in support of his atheism pass in review. Some of them are arguments that have occurred to me, as have Joad’s criticisms thereof.

An ex-Communist myself, I experienced my own recovery of belief about forty years ago. The work of relating my return to my recovery, however, is a work in progress. This blog may provide a platform for it.

When I chanced upon Sutton’s trilogy at a public library in the early ’70s, I was still viewing the world through Herbert Aptheker’s red-tinted spectacles. The massive amount of evidence of technology transfer that Sutton had discovered, organized, and published—under the imprint of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution—cohered with neither the Communist worldview I then held nor my anti-Communist one a few years later.

When I chanced upon Sutton’s trilogy at a public library in the early ’70s, I was still viewing the world through Herbert Aptheker’s red-tinted spectacles. The massive amount of evidence of technology transfer that Sutton had discovered, organized, and published—under the imprint of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution—cohered with neither the Communist worldview I then held nor my anti-Communist one a few years later.

His wife, Margit, had been an actress, and she had great beauty, intelligence, and presence as well.

His wife, Margit, had been an actress, and she had great beauty, intelligence, and presence as well.

For most of his life Joad was not only a socialist, but also a professed atheist who became dissatisfied with the worldview that underpinned that profession. He returned to the Church of England of his youth a few years before his death. (He never repented of his socialism, although he increasingly acknowledged, and feared, that the means to that end was a bloated and rights-violating state.) In The Recovery of Belief (1953) the many arguments he had relied on in support of his atheism pass in review. Some of them are arguments that have occurred to me, as have Joad’s criticisms thereof.

For most of his life Joad was not only a socialist, but also a professed atheist who became dissatisfied with the worldview that underpinned that profession. He returned to the Church of England of his youth a few years before his death. (He never repented of his socialism, although he increasingly acknowledged, and feared, that the means to that end was a bloated and rights-violating state.) In The Recovery of Belief (1953) the many arguments he had relied on in support of his atheism pass in review. Some of them are arguments that have occurred to me, as have Joad’s criticisms thereof.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, immersed in theological studies and spiritual formation between his profession of vows in 1924 and ordination in 1936, Lonergan produced that manuscript. In the ‘70s, after his methodological work was done, he returned to it.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, immersed in theological studies and spiritual formation between his profession of vows in 1924 and ordination in 1936, Lonergan produced that manuscript. In the ‘70s, after his methodological work was done, he returned to it.

Earlier that year I had dropped into Hook’s office at 25 Waverly Place to ask about the class. As a young Red, I couldn’t pass up the chance to meet this infamous anti-communist in the flesh.

Earlier that year I had dropped into Hook’s office at 25 Waverly Place to ask about the class. As a young Red, I couldn’t pass up the chance to meet this infamous anti-communist in the flesh.