(Continuing the series.)

When did Cyril Lionel Robert James become CLR? From his middle-class youth in colonial Trinidad, he was an omnivorous reader, starting with his mother’s library, drinking in classics from Shakespeare to Thackeray[1], but also history, while developing an intense interest in cricket, which he played and, more successfully, covered in the papers.

In his engrossing C. L. R. James in Imperial Britain, a scholarly study of six years of his subject’s life (1932–1938) between Tunapuna, Trinidad, and New York City, Christian Høgsbjerg notes James’s absorption of the age’s empire-friendly historical narrative. But then he found books that upturned such Received Opinion. Høgsbjerg quotes James from an October 1967 interview wherein James recalls what awakened his capacity for and interest in critical history.

I read an enormous amount of history books . . . chiefly the history of England and later, histories of Europe and ancient civilization. I used to teach history, and reading the lot of them, I gained the habit of critical judgment and discrimination . . . . I remember three or four very important history books. These were a history of England by G. K. Chesterton and some histories of the seventeenth century by Hilaire Belloc. These books violently attacked the traditional English history on which I had been brought up, and they gave me a critical conception of historical writing.[2]

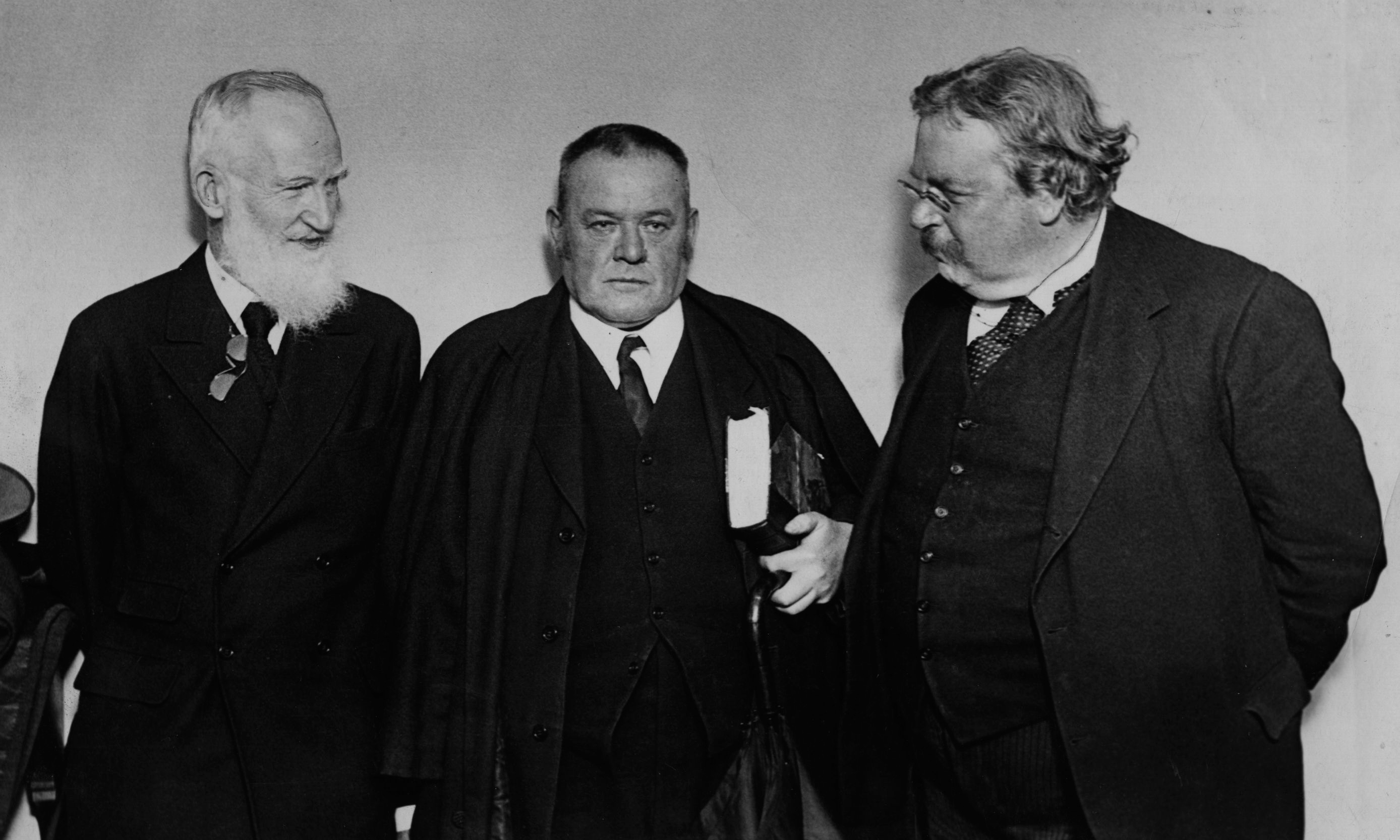

So, James, soon to become a revolutionary Marxist, cited Chesterton and Belloc, orthodox Roman Catholics of the post-Vatican I era, as the fons et origo of his critique of bourgeois historiography![3]

In the early 1930s, under the influence of Trotsky’s A History of the Russian Revolution, James began researching the Haitian revolution. (“At the end of reading the book, Spring 1934, I became a Trotskyist . . .” That is, after his expatriation to the UK, not while in Trinidad. See the October 1967 interview cited in note 2.) Yet as late as August 1933, caught up in the empire’s self-congratulatory celebration of the centennial of the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act,[4] James let these words be published under his name:

Our history begins with it [the Act]. It is the year One of our calendar. Before that we had no history.[5]

He would never make that kind of statement again.

He soon learned, on his own and through the scholarly labors of his former student (and, as future Prime Minister, jailer) Eric Williams (1911-1981), that the slave trade was not abolished because of its iniquity. It was abolished because the planter class had lost economic power. Human conscience just happened to awaken when slavery’s unprofitability became obvious to them.

To be continued.

Notes

[1] “Thackeray, not Marx, bears the heaviest responsibility for me.” C. L. R. James, Beyond a Boundary. Duke University Press, 1993 (1963).

Beyond a Boundary. Duke University Press, 1993 (1963).

[2] Høgsbjerg, 161, citing Richard Small, “The Training of an Intellectual, the Making of a Marxist,” in C. L. R. James: His Life and Work, ed. Paul Buhle, London: Allison and Busby, 1986, 49-60. This edition’s pagination, which Høgsbjerg used, that of this PDF, wherein Small’s article is on pages 13-18. James was probably referring to Chesterton’s A Short History of England (1917). One cannot know for sure which of Belloc’s books James had in mind, for among them are biographies of Charles I, Charles II, and James II, as well as a life of Cardinal Richelieu. He also wrote The French Revolution (1911), A History of England (1925), and Europe and the Faith (1920), which covers the 17th century’s broader context. Belloc was a splendid stylist.

[3] “George Bernard Shaw’s affectionate attack on G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, in an article entitled ‘The Chesterbelloc: A Lampoon,’ gave birth to a duomorph destined to find its place in literary legend. Chesterton and Belloc were seen so synonymously, said Shaw, that they formed ‘a very amusing pantomime elephant.’” Joseph Pearce, “The Chesterbelloc: Examining the Beauty of the Beast,” Faith and Reason: The Journal of Christendom College, Spring 2003. Take the link to download the PDF of this article.

[4] What was “abolished,” of course, was Britain’s involvement in the slave trade, on which “good will” the empire traded when they joined Europe’s “scramble for Africa” later in that century.

[5] C.L.R. James, “Slavery Today: Written by the Great-Grandson of a Freed Slave,” Tit-Bits [London], August 1933, 16. Cited in Høgsbjerg, 169. For zoomable, copyrighted image of that page, go here. Incidentally, “Høgsbjerg,” a Danish surname, is pronounced “Huh-s-BYUR” or “Huh-s-BYAHR.”