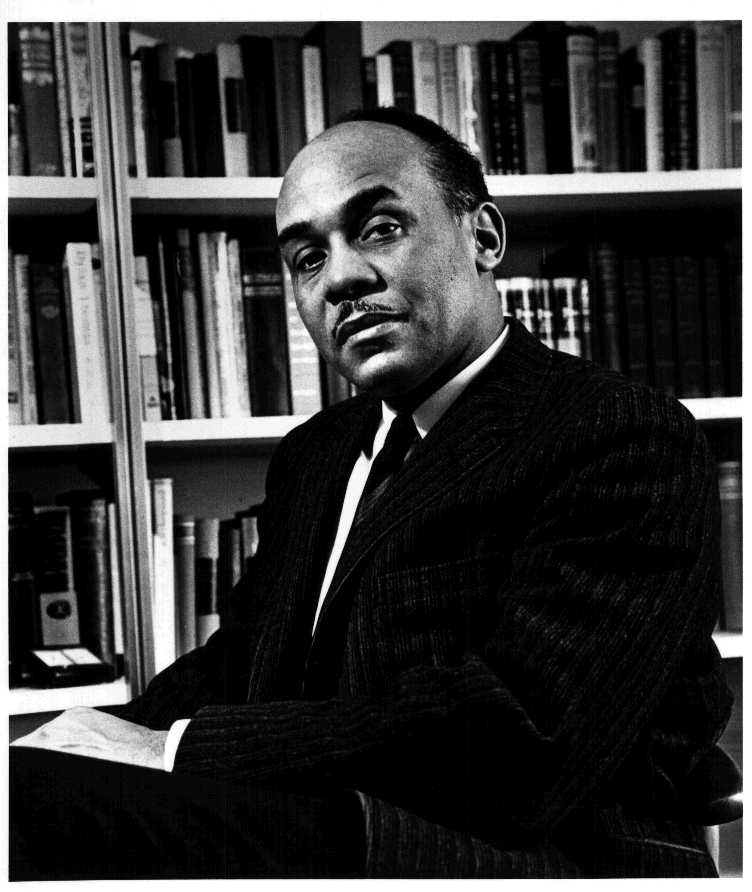

My 2013 essay on Herbert Aptheker’s ghosting of C. L. R. James which casts him as the former’s “invisible man” alludes, of course, to the title of Ralph Ellison’s great novel.[1] Today, as I was flipping through Arnold Rampersad’s life of Ellison, Aptheker’s name cropped up, although Ellison’s, like James’s or Richard Wright’s, never did in any of our many chats in his office. Culturally prominent African Americans whom Aptheker knew, once they were “on the outs” with his party, were to him personae non gratae, regardless of their achievements.

My 2013 essay on Herbert Aptheker’s ghosting of C. L. R. James which casts him as the former’s “invisible man” alludes, of course, to the title of Ralph Ellison’s great novel.[1] Today, as I was flipping through Arnold Rampersad’s life of Ellison, Aptheker’s name cropped up, although Ellison’s, like James’s or Richard Wright’s, never did in any of our many chats in his office. Culturally prominent African Americans whom Aptheker knew, once they were “on the outs” with his party, were to him personae non gratae, regardless of their achievements.

Such were the choices [Rampersad writes] facing Ralph as he found himself fallen among radicals in New York [in the mid-1930s]. He probably became, at least for a while, a dues-paying [Communist] party member. Herbert Aptheker, a scholar and Communist who knew Ralph from these years and believed that he was a fellow member, recalled that “it was really easy to join the Party. You simply signed up. Ralph would not have had to submit to tests or special study or anything like that. He would have been welcomed right away.”[2]

[Ellison] received a note . . . asking him to contribute an essay to a new journal of African-American affairs, to be sponsored by the recently formed Negro Publication Society. The society, tightly linked to the radical left, included the young Communist historian Herbert Aptheker, the black intellectuals Arthur Huff Fauset and Alain Locke, the dramatist Marc Blitzstein, the novelist Theodore Dreiser, the artists Rockwell Kent, and Henrietta Buckmaster . . . . The most celebrated person involved was the proposed editor of the journal, Angelo Herndon . . . .

Now, in 1941, as secretary of the Negro Publication Society, he [Ellison] was the editor of The Negro Quarterly: A Review of Negro Life and History. . . . Ralph would insist later that Herndon published the magazine in defiance of the Party, which presumably saw it as a diversion from its goal of uniting blacks and whites in the war effort. [3]

In March 1942, then Herndon launched the journal . . . he invited Ralph. . . . He liked the look of the first number. Dominated by a long, heavily footnoted article on slavery[4] by Aptheker, it projected an image of seriousness, if not severity. Either at this party or shortly afterward, Ralph agreed to join the staff as managing editor at a salary of $35 a week.[5]

[Ellison] declined to attend a conference called by the leftist Harlem Writers Guild at the New School for Social Research. Partly as a result, he became its prize scapegoat, attacked by writers such as [John Oliver] Killens, John Henrik Clarke, and Herbert Aptheker.[6] 423

In other words, Aptheker gave Ellison the same treatment he gave ex-comrade Wright and for the same reason: there’s no lower form of life than a renegade from the cause of revolution.[7]

Notes

[1] Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man, Random House, 1952. My essay is anthologized in Herbert Aptheker: Studies in Willful Blindness, self-published, 2019.

[2] Arnold Rampersad, Ralph Ellison: A Biography, Knopf, 2008, 93; from Rampersad’s interview of Aptheker, June 25, 2001.

[3] Rampersad, Ellison, 152.

[4] To the inaugural issue of The Negro Quarterly: A Review of Negro Life and History, Spring 1942, Aptheker  contributed “The Negro in the Abolitionist Movement.” That is, it was about African American resistance to slavery. That year, International Publishers published that essay as a booklet; Aptheker anthologized it in his Essays in the History of the American Negro, International Publishers, 1945, 1964. Note that Doxey Wilkerson‘s “Negro Education and the War” is the first article in the first issue.

contributed “The Negro in the Abolitionist Movement.” That is, it was about African American resistance to slavery. That year, International Publishers published that essay as a booklet; Aptheker anthologized it in his Essays in the History of the American Negro, International Publishers, 1945, 1964. Note that Doxey Wilkerson‘s “Negro Education and the War” is the first article in the first issue.

[5] Rampersad, Ellison, 153.

[6] Rampersad, Ellison, 423.

[7] Anthony Flood, “Did Richard Wright want to ‘kiss the hand of the man who wrote American Negro Slave Revolts”? Yes, according to that hand’s owner. Notes on a mutual suspension of hostilities,’ June 1, 2025.

America: A Critique of Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma (1946) and reviewed it six years later in a party periodical that Aptheker edited, it was odd that Aptheker omitted mention of Comrade Wilkerson’s review when preparing for publication the first critical scholarly edition of Du Bois’s 1952 In Battle for Peace.

America: A Critique of Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma (1946) and reviewed it six years later in a party periodical that Aptheker edited, it was odd that Aptheker omitted mention of Comrade Wilkerson’s review when preparing for publication the first critical scholarly edition of Du Bois’s 1952 In Battle for Peace. . . . Unlike other reviewers, however, Wilkerson’s incisive Marxist analysis registered important critiques of the book. First, he held that Du Bois’s use of the term socialism captured all forms of “public ownership” instead of focusing on “collective ownership” with “working class control of the state.” In other words, for Wilkerson’s tastes, Du Bois’s radical discourse lacked theoretical precision and the finer points of communist doctrine over which Party members sparred.

. . . Unlike other reviewers, however, Wilkerson’s incisive Marxist analysis registered important critiques of the book. First, he held that Du Bois’s use of the term socialism captured all forms of “public ownership” instead of focusing on “collective ownership” with “working class control of the state.” In other words, for Wilkerson’s tastes, Du Bois’s radical discourse lacked theoretical precision and the finer points of communist doctrine over which Party members sparred.

Communism,”

Communism,”

[1]

[1] Dangerous Communist in the United States”: A Biography of Herbert Aptheker

Dangerous Communist in the United States”: A Biography of Herbert Aptheker

As an editor and bibliophile, I agree with the many critics of this book’s infelicities (typos, organizational issues, lack of index, and so forth). Nevertheless, I thank God James Heartfield wrote it, that he spilled his cornucopia of insights out of his head and onto paper. Let some publisher step forward to polish its contents so it passes conventional muster. Until then, however, students of this endlessly fascinating subject should benefit from the author’s vast knowledge of how things hung together eighty and ninety years ago—I say this even though the underlying worldview is not mine.

As an editor and bibliophile, I agree with the many critics of this book’s infelicities (typos, organizational issues, lack of index, and so forth). Nevertheless, I thank God James Heartfield wrote it, that he spilled his cornucopia of insights out of his head and onto paper. Let some publisher step forward to polish its contents so it passes conventional muster. Until then, however, students of this endlessly fascinating subject should benefit from the author’s vast knowledge of how things hung together eighty and ninety years ago—I say this even though the underlying worldview is not mine.  History, 1600–2020, 2022; The Blood-Stained Poppy: A critique of the politics of commemoration, 2019; and The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 2016—to cite a few), Heartfield gives off no whiff of the Olympian stuffiness of many academics, as we expect of the lecturer we find on YouTube. I recommend watching his 2016 talk on C.L.R. James and the Left’s opposition to taking sides in the Second World War and the ethical issues that opposition posed. Heartfield’s reference (on page 151) to James’s 1940 penny-pamphlet “My Friends” A Fireside Chat on the War—written under the pseudonym “Native Son” (which momentarily confused me, since in 1940 Native Son’s author, Richard Wright, was still a “The Yanks Aren’t Coming” Stalinist)—led me happily to the tattered copy available on archive.org.

History, 1600–2020, 2022; The Blood-Stained Poppy: A critique of the politics of commemoration, 2019; and The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 2016—to cite a few), Heartfield gives off no whiff of the Olympian stuffiness of many academics, as we expect of the lecturer we find on YouTube. I recommend watching his 2016 talk on C.L.R. James and the Left’s opposition to taking sides in the Second World War and the ethical issues that opposition posed. Heartfield’s reference (on page 151) to James’s 1940 penny-pamphlet “My Friends” A Fireside Chat on the War—written under the pseudonym “Native Son” (which momentarily confused me, since in 1940 Native Son’s author, Richard Wright, was still a “The Yanks Aren’t Coming” Stalinist)—led me happily to the tattered copy available on archive.org.