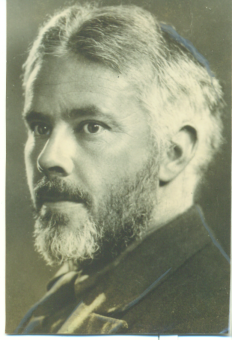

Knowing that the paths of two intellectual heroes, Lord Acton and Alfred North Whitehead, crossed at Cambridge, I’ve sometimes imagined Whitehead, whose mathematics fellowship (1888-1910) overlapped Acton’s Regius Professorship of Modern History (1895-98), attending his lectures.

We know that while at Cambridge Whitehead showed interest in history and theology. But did they meet? The truth may be lost to history.

Lowe’s life of Whitehead documents that he admired Acton, was aware of his “troubles with Rome,” proposed a Cambridge memorial to him, and dropped “in on some of his lectures after Acton was appointed” to the Regius chair. (p. 186) “But I know of no discussions between them,” Lowe  wrote.

wrote.

Like Isaac Newton and Francis Bacon before him, Acton had rooms in Nevile’s Court. In his Lord Acton Roland Hill states that the designation of his room was “staircase 2, A1, on the first floor. (His library would later occupy the apartment next door.) When Whitehead married [in 1891], he changed the rooms given him by Trinity College, moving from a large, high-ceilinged room (C2) in Nevile’s Court to a modest one there” until 1902, the year of Acton’s death.

During the years of the lectures, therefore, Acton and Whitehead were “next-door neighbors.” Someone with access to Nevile’s Court’s floor plans could judge the proximity of their rooms to each other.

Lowe mentioned that in the mid-1890’s the philosopher J. M. E. McTaggart formed Eranos, a discussion group and that Whitehead was a member, but he did not think much of it. James C. Holland, in his introduction to Owen Chadwick’s study of Acton, noted that “it was at Cambridge that he gave it [i.e., “his commitment to moral judgment in history”] definitive and final expression, in May, 1897, in the privacy of his Trinity rooms in Nevile’s Court, where he [Acton] addressed a select society, the Eranus [sic], which never numbered more than twelve members.”

The author achieves this in about the same number of pages (at least, sans apparatus) but, more importantly, he does so with equal readability, all the more remarkable since English is not his mother tongue.

The author achieves this in about the same number of pages (at least, sans apparatus) but, more importantly, he does so with equal readability, all the more remarkable since English is not his mother tongue.

When I chanced upon Sutton’s trilogy at a public library in the early ’70s,

When I chanced upon Sutton’s trilogy at a public library in the early ’70s,  His wife, Margit, had been an actress, and she had great beauty, intelligence, and presence as well.

His wife, Margit, had been an actress, and she had great beauty, intelligence, and presence as well.

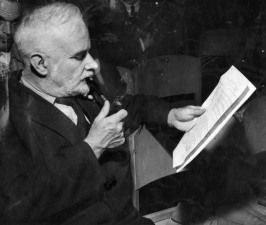

For most of his life Joad was not only a socialist, but also a professed atheist who became dissatisfied with the worldview that underpinned that profession. He returned to the Church of England of his youth a few years before his death. (He never repented of his socialism, although he increasingly acknowledged, and feared, that the means to that end was a bloated and rights-violating state.) In The Recovery of Belief (1953) the many arguments he had relied on in support of his atheism pass in review. Some of them are arguments that have occurred to me, as have Joad’s criticisms thereof.

For most of his life Joad was not only a socialist, but also a professed atheist who became dissatisfied with the worldview that underpinned that profession. He returned to the Church of England of his youth a few years before his death. (He never repented of his socialism, although he increasingly acknowledged, and feared, that the means to that end was a bloated and rights-violating state.) In The Recovery of Belief (1953) the many arguments he had relied on in support of his atheism pass in review. Some of them are arguments that have occurred to me, as have Joad’s criticisms thereof.

As its preface drew to a close, I noticed that the author’s eloquent affirmation of purpose, excitement and hope betrayed hardly any awareness of limitations. Here are the words of a man undertaking a massive project in his fiftieth year, in the aftermath of Wall Street’s collapse, the memories of the Great War still fresh in his readers’ minds as the winds of its successor begin to blow in Europe. Where the latter will soon take Western Civilization, of course, he does not predict:

As its preface drew to a close, I noticed that the author’s eloquent affirmation of purpose, excitement and hope betrayed hardly any awareness of limitations. Here are the words of a man undertaking a massive project in his fiftieth year, in the aftermath of Wall Street’s collapse, the memories of the Great War still fresh in his readers’ minds as the winds of its successor begin to blow in Europe. Where the latter will soon take Western Civilization, of course, he does not predict:  In the aftermath of the Great Depression, immersed in theological studies and spiritual formation between his profession of vows in 1924 and ordination in 1936, Lonergan produced that manuscript. In the ‘70s, after his methodological work was done, he returned to it.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, immersed in theological studies and spiritual formation between his profession of vows in 1924 and ordination in 1936, Lonergan produced that manuscript. In the ‘70s, after his methodological work was done, he returned to it.