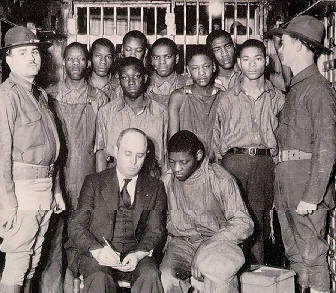

Ninety-three years ago today, nine Black teenagers, “hoboing” on a freight train between Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee, were attacked by a mob of white youths who strongly disapproved of their presence on “a white man’s train.” Thrown off it by their intended victims, the hooligans falsely reported to police in Paint Rock, Alabama, that the teenagers has attacked them. After a search of the train, the police rounded up not only the Black youths but also two white women who then falsely accused them of rape. The prosecution of “The Scottsboro Boys,” the first international cause célèbre of the American Civil Rights Movement, afforded an opportunity for the Communist Party to leave its mark, the first of many, on that movement. This complex historical episode eventually became the subject of academic study, and one of the first scholars to study it was my friend and fellow Aptheker research assistant, Hugh Murray. [1]

On that very day, March 25, 1931, Otis Q. Sellers turned 30. He was not yet the grey eminence I knew in the 197os, but the young man finally out of his twenties and on his way to becoming the Bible teacher from whom I learned much. About his life and thought I’ve been blogging into existence, for the past six years, a 96,000-word manuscript. (I’m raising funds to publish it as a book, I hope this year.) Two years into the Great Depression, Sellers was in the middle of his stint (1928-1932) as pastor of Fifth Avenue Baptist Church in Newport, Kentucky, which he left (to shorten a long story brutally) “to do my own studies.” On his milestone birthday, what was transpiring 400 miles south of him was on the mind of few Americans, and his wasn’t one of them. That would soon change.

Continue reading “Otis Q. Sellers, the Scottboro Boys, and me”

In a

In a

Listening this morning to an old (well, 2022) podcast[1] by the great Calvinist apologist James R. White, I was startled by his reference to Thom Notaro’s 1980 Van Til and the Use of Evidence. (White says he paid $3.75 for his copy back in the day, but a used copy on Amazon will set you back forty-five bucks.) Startled, I say, because over forty years ago, the Roman Catholic periodical New Oxford Review published, in its November 1981 issue, pages 29-30, my cluelessly negative review of Notaro’s book.

Listening this morning to an old (well, 2022) podcast[1] by the great Calvinist apologist James R. White, I was startled by his reference to Thom Notaro’s 1980 Van Til and the Use of Evidence. (White says he paid $3.75 for his copy back in the day, but a used copy on Amazon will set you back forty-five bucks.) Startled, I say, because over forty years ago, the Roman Catholic periodical New Oxford Review published, in its November 1981 issue, pages 29-30, my cluelessly negative review of Notaro’s book.

In any case, I find myself enjoying their reaction to the money-making notes that I see coming (having seen the videos hundreds of times). The females, black and white, American, European, and Asian, invariably melt, even shed tears. Sometimes their accents make their English unintelligible to me, but the emotion is undeniable. Some male viewers, rendered speechless, are content in that silence; others, metaphysically shocked. “I thought they were black,” some mutter, followed by “Soul got no color!” or the equivalent.

In any case, I find myself enjoying their reaction to the money-making notes that I see coming (having seen the videos hundreds of times). The females, black and white, American, European, and Asian, invariably melt, even shed tears. Sometimes their accents make their English unintelligible to me, but the emotion is undeniable. Some male viewers, rendered speechless, are content in that silence; others, metaphysically shocked. “I thought they were black,” some mutter, followed by “Soul got no color!” or the equivalent.