That’s the question underlying my current project. Answering it might explain why I was drawn to revolutionary Marxism (of interest at least to me, if not to you). Youngsters can be at once hypercritical and credulous. Revolutionary rejecters of the existing order, they fall for one or another “explanation” hook, line, and sinker.

Rummaging through the lives of Marxist intellectuals is no mere romantic, antiquarian interest of mine (although it is partly that). I will draw upon but not add to the biographies already written. I’m trying to understand, to the extent it is intelligible, the demonic madness we see on college campuses, draped in the language of moral outrage. (“F— finals! Free Palestine!,” announced one savage disrupting Columbia University students who were trying to use the main library to prepare for final exams, to cite only one example. I find the categories of intelligibility in Christian theology, specifically anthropology.

Created in God’s image and living in His world as (we all are), the miscreants have a sense of moral outrage (however misinformed), but they have nothing in which to ground it. On Monday, they’ll affirm that it’s wrong to starve children; on Tuesday, that an unborn child’s natural protector has the right to procure the services of an abortionist to destroy that child chemically, or cut him or her to pieces, or leave him or her to expire on a metal table. Most of them, if pressed, will say that, strictly speaking, we don’t know that we have more moral dignity than that of “evolved,” i.e., rearranged, pond scum. They merely dogmatize that we do.

I’m stepping back from the news and noise of the day to reflect on more civilized specimens of humanity, however much their careers betrayed the civilizing impulse. I want to explore why they thought Marxist revolution adequately addressed the moral outrage of interracial subjugation, cruelty, and savagery, evils that energized them? That it was such an answer is the conclusion at which my three very different intellectuals arrived. It all starts with outrage at one or another fact in one man’s experience: colonialism, imperialism, slavery, peonage, Jim Crow.

I will also ask whether these men, if they were alive today, would embrace today’s savages. I fear they would have, as counterintuitive as such a conclusion might strike some.

The dialectical materialism that they (and I) embraced has no way to deal with any norms at all, let alone moral norms: the universe is an indifferent aggregate of material facts or events assumed to be a system but never knowable as such on the basis of materialism. A social system does not explain moral turpitude. The Marxist has to borrow from the Christian worldview he rejects to have any hope of understanding the roots of the moral outrage that sets him on his moralistic quest, a quest over which he drapes the mantle of “science.”

So, it may strike some as odd that I undertake to write about what three writers, born before the Great War and the Bolshevik Revolution and shaped particularly by the latter, did with their lives, rejecting as they did the Gospel of Jesus Christ. It is odd, however, only if one discounts my interest in what one does with one’s life, what I did with mine, and the similarities (at a great distance in terms of output and value) between the latter and the former.

I knew Aptheker fairly well. Under his strong intellectual influence, my late teenage mind was shaped, or rather, I allowed it to be so shaped. I’m going to think out loud about their professed indifference, if not hostility, to Jesus Christ. This indifference, a reflection of their and our age’s general secularism, rendered their writings and the thought they embody ultimately vacuous.

Of the three, one was white, the other two, black. James enjoyed a middle-class, Anglican upbringing in Trinidad, surrounded by books, which he devoured and (in many cases memorized).

Aptheker, the son of a businessman affected by the Crash of ’29—which forced him to let go of his Trinidadian maid[1]—was drawn to the life of the mind, but initially to science (geology), not history. She was, he recalled, “decisive” in his life. But his 1932 trip to the Jim Crow South with his father on a business trip began to shift his interest. But when he entered Seth Low, he

was very interested in geology and was good at it. The professor asked me to join him in a summer trip to Italy to look for oil. And then it occurred to me, if we found oil, it would be for Mussolini! But if I found oil here, it would be for Rockefeller. . . . But I always loved history. I got my bachelor’s degree as a bachelor of science, because I was in geology, astronomy and so on, chemistry; I moved into a master’s program in history and wrote my thesis on Nat Turner.[2]

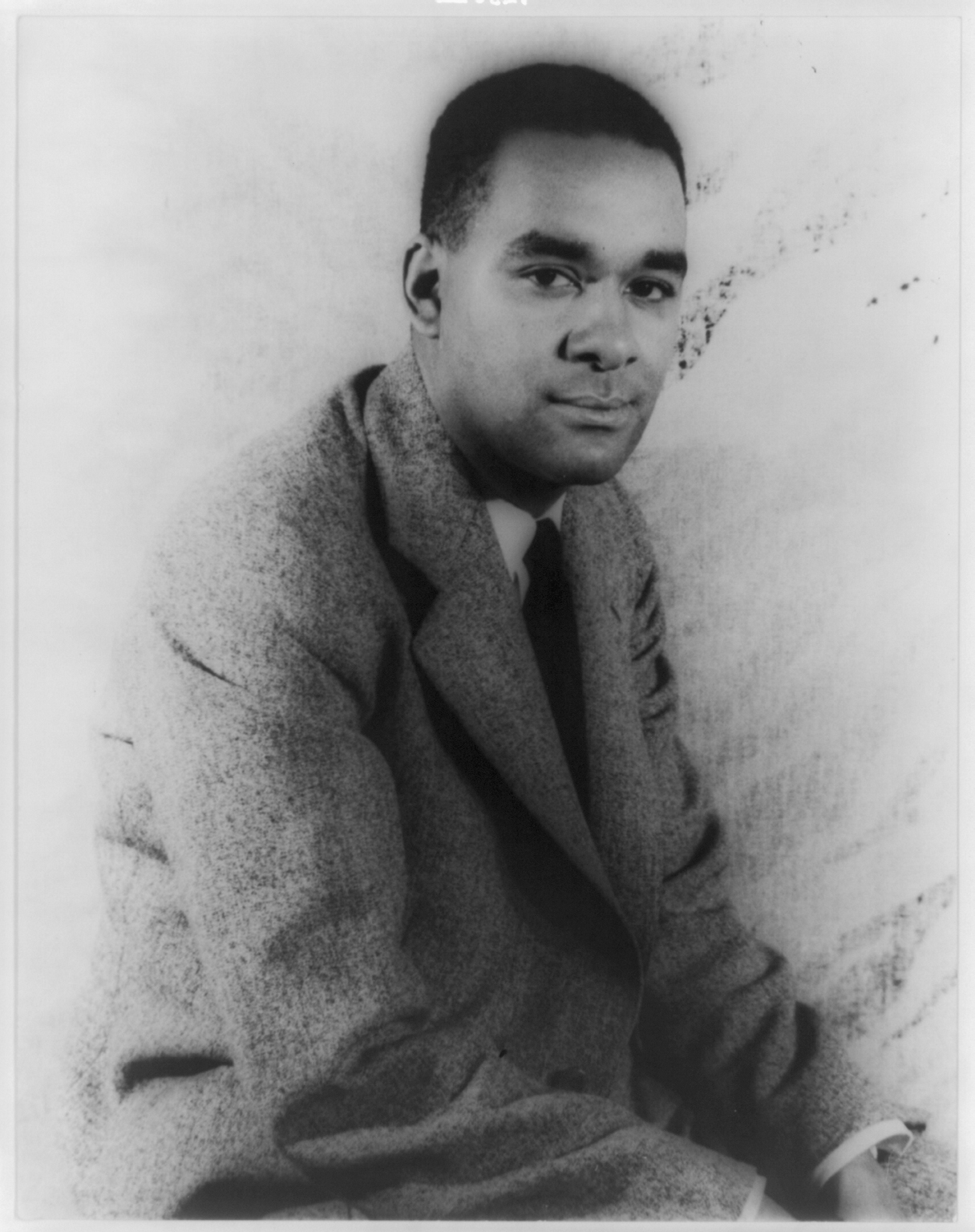

By marked contrast, Wright grew up hungry and dirt poor in Natchez, Mississippi and fought for every opportunity to read (and eat). Ironically, his writings would earn more money and status than the other two gents combined. He was raised under the watchful eye of his Seventh Day Adventist grandmother, whose way of showing concern for him only reinforced his distaste for religion and gave him no reason to soften his hostility. His individualist cast of mind was energized by his discovery of social critic H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) who cordially hated the culture that had treated Wright like dirt. To borrow Mencken’s books from the segregated public library on a sympathetic Irishman’s wife’s library card, Wright forged racially self-deprecating notes to be read by the librarian. That led him first to Mencken’s books and then to the classics Mencken referred to.

James had no trouble acquiring books. A voracious reader from a young age, James, the son of schoolteachers, would re-read books multiple times, like Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, often memorizing long passages. In a room filled with books and other art, he also devoured a wide range of literature, history, music, and art, including our common civilization’s foundational texts. He won a scholarship in 1910 to Queen’s Royal College (QRC), the island’s oldest non-Catholic secondary school, in Port of Spain, where he became a club cricketer, distinguished himself as an athlete (he held the Trinidad high-jump record from 1918 to 1922), and also began to write, at first on cricket.

To be continued.

[1] James came from a relatively well-educated, middle-class Creole background. In 1932, he emigrated to England, where he became involved in Marxist politics and the African and West Indian independence movements. Angelina Corbin, a Trinidadian immigrant, worked as a live-in domestic worker for also well-to-do family of Herbert Aptheker, in Brooklyn in the 1920s and 1930s until the Crash of ’29 forced her dismissal.

[2] Interview of Herbert Aptheker by Robin D. G. Kelley, Journal of American History, Volume 87, Issue 1, June 2000, 151, https://doi.org/10.2307/2567920

Related Posts

-

- “C. L. R. James: First Amazon Review of New Biography,” December 3, 2022.

- “C.L.R. James: still Stalinism’s ‘Invisible Man,’” June 30, 2021.

- “Revisiting Herbert Aptheker’s pattern of misrepresentation and omission,” February 26, 2021.