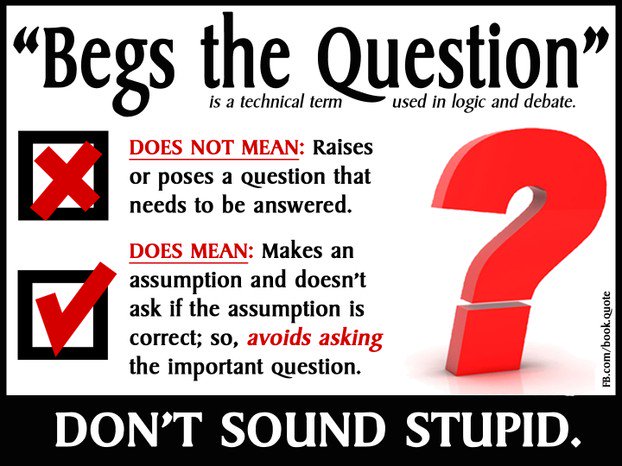

Do apologists for the Christian worldview “beg the question”? That is, do we assume as true what we’re arguing about rather than deduce it from propositions shared by the people we’re arguing with?

No. Ironically, this charge of begging the question (petitio principii) commits the fallacy of missing the point (ignoratio elenchi).

The point? Asking questions has conditions. The Christian worldview apologist asks about the necessary characteristics of a world that fulfills those conditions. (Some might discern the “transcendental” direction of this query. It is not a “garden variety” investigation.)

The charge of begging the question here, when it’s not a dodge, reflects a failure to understand the relationship of a worldview to its component beliefs. A worldview is neither the premise nor the conclusion of a syllogism. One’s worldview will, however, make syllogistic reasoning itself possible or impossible.

To self-consciously affirm and defend one’s worldview is to bring to the foreground what is usually in the background. Its vindication is indirect; so must be any effort to discredit it.

The Christian worldview apologist draws attention to features of the experience of his or her dialectical adversary. Noting that we all take those features and their interdependence for granted, the apologist invites the critic to stop taking them for granted, at least for the duration of the conversation.

That is, the apologist bids the critic to reflect on how these radically diverse aspects can possibly comport with each other in the same world.

The apologist claims that (a) the Triune God of the Christian scriptures is the primary, indispensable member of that network of truths we take for granted and (b) that the critic suppresses awareness of that indispensable member. According to the apologist’s theology, the suppression has a psychological driver: the suppression is “unrighteous.” (Romans 1:18-20)

This is not to “psychoanalyze” the critic ad hominem, but rather to lay out what follows from the denial of God’s self-revelation in creation and scripture.

When we ask questions, we bring into play (at least) two disparate things, each of them irreducible to the other(s). For one, we value truth. For another, in the pursuit of truth, we draw conclusions from premises.

Now, logic and the pursuit of truth are intimately related and inseparable in our experience, but they are as different from one another as any two things can be. How is it that they (to name no other features of our experience) comport with each other or “hang together”? (Colossians 1:17)

Let’s add to these our incorrigible belief in a world populated with people like us. We don’t “infer” its existence or theirs: we intuit it. The first sentence of every article or book presupposes the truth of this intuition.

This intuition is not identical with the ability think logically or value truth, yet we cannot have that intuition apart from the other two.

Then there’s our (fallible, yet more or less reliable) memory of people, places and things.

We also detect and remember patterns in their behavior; we depend on our (imperfect, yet corrigible) grasp of them. That is, we generalize about nature’s regularity. For theoretical as well as practical purposes, we act on that law-like behavior. We assume it even as we investigate it.

We also generalize, more or less reliably, about other persons as persons, as selves with memories, fears, loves, hatreds, and so forth. We vary in our capacity for empathy and sympathy, but (except in the psychotic) it’s there.

And our “person-realism” is no more deducible or otherwise inferable from our nature’s logical side from our capacity to evaluate; or either is from our inductive ability; or either is from our realism about the world and the many who are “not me.”

We take these radically different yet mutually comporting things for granted every waking minute of every day. What is the justification for taking for granted a network of basic beliefs that functions as a worldview?

Or is question-begging all right as long as we’re begging a lot of them all at once all the time?

We not only take a boatload of things for granted, but we even take taking-for-granted itself for granted. Either the importance of stopping escapes us, or we simply wish to put off the consequence of stopping.

They say when you take things for granted, the things you are granted get taken. That’s one way to describe the apologist’s challenge to the unbeliever, except the former wants to put the taking on a firm foundation.

The love of truth is experienced as exigency or “demandingness” when we try to express ourselves clearly and marshal evidence for a judgement.

Whence that exigency? Natural selection?

When one argues about worldviews, it seems arbitrary not to ask those questions. Does arbitrariness—an evasion of rational exigency—get a pass here?

These wildly disparate aspects—logic, the love and pursuit of truth (and other absolute values), world-realism, person-realism, pattern-grasping, the reliability (and fallibility) of memory—form a network of what the late Greg Bahnsen called “non-negotiables”: we won’t give up any of them. Apart from that network, none is intrinsically intelligible.

Exactly one network of non-negotiable beliefs, argues this Christian apologist, adequately explains the unity required by this diversity because it identifies and affirms its one absolutely indispensable member: the Triune God of the Bible.

The vindication of that claim proceeds not by direct proof—the question, after all, is: what are the conditions of proof—but by eliminating rival worldviews. (Let the critics pick their poison.)

The latter are serially shown to be narratives that attempt to substitute for—and, failing that, distort—our birthright worldview, that is, the worldview or “light” that is divinely programmed into each human being as he or she comes into the world. John 1:14.

This light is the basic network of beliefs we work with from childhood through adulthood. No alternative worldview permits intelligible predication. That’s a big deal.

Since the Christian worldview implies that it alone makes predication possible, the apologist, consistent with his commitment to it, challenges critics to show either (a) the Christian worldview doesn’t make intelligible predication possible or (b) another worldview does.

The birthright worldview operates in all of us. We’re created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27), even of the Logos of God (John 1:1), that we might subdue creation under God.

One may not like that account, but it at least it’s an account.

What can the critic offer in its place? A variant of monism, dualism, pluralism, materialism, idealism, empiricism or some other exercise in abstractions gone wild?

Everyone, tacitly or openly, relies on this birthright worldview; some foolishly negotiate their intellectual business on the basis of an antithetical worldview. But the very intelligibility of denial only makes sense if the Christian worldview is true. Let me explain.

Predication—the assertion that something is the case or has certain attributes—is possible only if the unity among these things does not erase their diversity and that the latter diversity doesn’t shatter that unity.

If the unity or “oneness” of all things is ultimately real, then any diversity among them is only apparent. It’s not the truth of things. It’s as simple as that.

It is equally true (and simple), however, that if diversity is ultimately real, then any apparent unity among the diverse many distorts the truth.

Unity and diversity are polar opposites, yet they are involved in the interpretation of our experience at every level. Only at our mind’s peril do we allow one to negate the other. These abstractions repel each other, and yet we never find an instance of one that involved with the other.

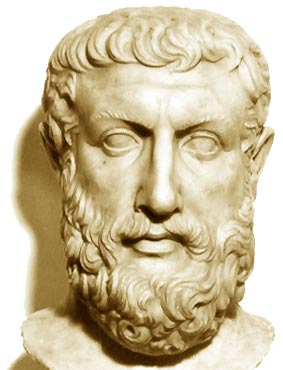

The attempt to reconcile unity and diversity by eliminating one or the other (by perhaps dissolving the one into the many or the many into the one) is the story of philosophy, certainly of its Western branch, conveniently summed up in the antithesis between the ideas of Parmenides of Elea (b. circa 515 BC) and those of Heraclitus of Ephesus (b. circa 535 BC).

For Parmenides, the only intellectually safe ground is the affirmation “Being is; non-being is not,” which rules out becoming or change as unreal.

Heraclitus took the opposite tack: “All is flux.” Everything changes, in which case every unity of parts, every continuity of phases that we affirm is an illusion, a mere appearance. Ultimately, there is no whole, only an aggregate. A pile.

There is no reason to favor or elevate either abstraction over the other. On the contrary, there’s an excellent reason not to: they’re both involved in the inception of our every predication, silent or shared.

To consign either unity or diversity to the realm of unreality or illusion is to destroy the possibility of intelligible predication, even if the consignor persists in predicating.

Unity and diversity are correlatives like “husband” and “wife”: can’t have one without the other. Neither can be understood apart the other. Since they repel each other logically, they cannot co-exist in reality. Unless . . .

Unless what is in back of everything is the creator of all things in Whom unity and diversity are equally ultimate.

And that sums up the Triune God of scripture, the godhead reflected in His creation and Who placed His image-bearer in it and authorized him to cultivate it. Three co-equal persons in one indivisible godhead satisfies the need for an equally ultimate one and many.

But why exactly three persons? Why not two? Why not more than three? Wouldn’t two, four or more persons form a diversity equally ultimate with the godhead’s unity?

To be continued.