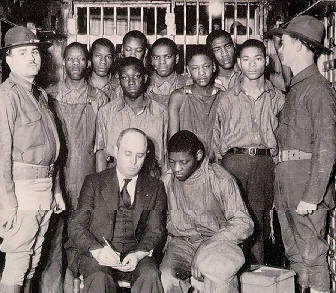

Ninety-three years ago today, nine Black teenagers, “hoboing” on a freight train between Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee, were attacked by a mob of white youths who strongly disapproved of their presence on “a white man’s train.” Thrown off it by their intended victims, the hooligans falsely reported to police in Paint Rock, Alabama, that the teenagers has attacked them. After a search of the train, the police rounded up not only the Black youths but also two white women who then falsely accused them of rape. The prosecution of “The Scottsboro Boys,” the first international cause célèbre of the American Civil Rights Movement, afforded an opportunity for the Communist Party to leave its mark, the first of many, on that movement. This complex historical episode eventually became the subject of academic study, and one of the first scholars to study it was my friend and fellow Aptheker research assistant, Hugh Murray. [1]

On that very day, March 25, 1931, Otis Q. Sellers turned 30. He was not yet the grey eminence I knew in the 197os, but the young man finally out of his twenties and on his way to becoming the Bible teacher from whom I learned much. About his life and thought I’ve been blogging into existence, for the past six years, a 96,000-word manuscript. (I’m raising funds to publish it as a book, I hope this year.) Two years into the Great Depression, Sellers was in the middle of his stint (1928-1932) as pastor of Fifth Avenue Baptist Church in Newport, Kentucky, which he left (to shorten a long story brutally) “to do my own studies.” On his milestone birthday, what was transpiring 400 miles south of him was on the mind of few Americans, and his wasn’t one of them. That would soon change.

Sellers followed the news, but to his studies in the Word it took a distant second place. He had no particular interest in civil rights, but from what I’ve been able to uncover, he didn’t harbor the anti-Black animus that suffused the country’s climate of opinion. His daughter, Jane (1927-2020), shared this vignette with me:

Although our country was certainly divided racially in my growing-up years, I never saw any evidence of it in my family. I didn’t even notice, was not aware, how things really were. Neither of my parents considered race as a factor in dealing with anyone. In Grand Rapids [i.e., after 1936], we lived a couple of blocks from a lake. (Land of 5,000 lakes) At the lake was a small amusement park with a few rides, a summer theater, a roller rink. Mother and I would often walk up to the lake on summer evenings when Dad was out of town. One evening Mother started talking to a Black couple who were at the Ferris wheel. They had a baby. “Would you like to go on the ride?,” my mother asked. They answered Yes, but they had the baby. Mother reached out, took the baby, and told them to go ahead and enjoy themselves. At the time I was not aware of what had just happened, but as I grew older and learned about race relations, I knew on that evening I had discovered something wonderful about my mother. (Email to me, April 3, 2019)

Apart from God’s eternal decree of whatever comes to pass, these disparate stories connect, as far as I can see, only through me and my interests. Thanks for indulging me.

Note

[1] At Tulane University, where his papers are deposited, Murray wrote his Master’s thesis on this case. In its original advertisement for the documentary, Scottsboro: An American Tragedy, Public Broadcasting Service had suggested “For Further Reading” three of his essays (originally chapters of his thesis): “The NAACP versus the Communist Party: The Scottsboro Rape Cases, 1931-1932,” Phylon, Vol. 28, No. 3 (3rd Qtr., 1967); “Aspects of the Scottsboro Campaign,” Science & Society, 35:2, Summer 1971, 177-192; “Changing America and the Changing Image of Scottsboro,” Phylon, Vol. 38, No. 1 (1st Qtr., 1977). The Study Guide for The Scottsboro Boys, the Broadway musical that opened at New York’s Lyceum Theater on October 31, 2010, cites the first of these papers twice (on page 16); more recently, Kenan Malik lists it in his bibliography for Not So Black and White: A History of Race from White Supremacy to Identity Politics, London, 2023.