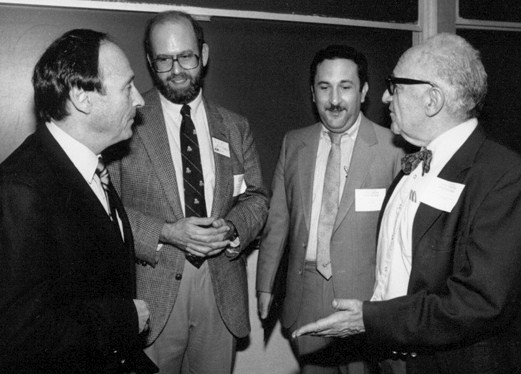

I wished Herbert Aptheker a happy 60th in person in 1975 and called Isaac Asimov on his five years later. I had just finished reading the latter’s memoir, his number was listed, and he answered immediately and amiably. I also participated in Murray Rothbard’s surprise celebration (same milestone) in 1986.

For mine in 2013, my wife and I went to Nam Wah Tea Parlor on Chinatown’s Doyers Street on the recommendation of Mark Margolis, the recently deceased actor with whom only the week before we had shared a common table (i.e., with “strangers”) at Joe’s Shanghai (around the corner on Pell Street).

For me, reaching 70 has not been like hitting 60. I’m neither living nor working where I was then; I had no clue of how (if ever) those transitions would go. Between then and now I got a few things published, books that had been pipedreams and might have remained so. Herbert lived to 87; Isaac, 71; Murray never made it to 69. Each man finished many projects, but also left some unfinished. I’m thinking especially of the “missing” (that is, unwritten) third volume of Murray’s history of economic thought.

I remember talking about Asimov’s books to a youngster working in the mailroom of Sargent Shriver’s law firm. He was stunned to learn that Asimov was a person: the spines of hundreds of books in his school’s library bearing Asimov’s name suggested the name of a publishing house.

Aptheker is and will be (except perhaps for his progeny and the dwindling number of those who knew him) a subject of specialized interest, a function of a broader interest in Africana studies and Communism.

Of these three, only the writings of the polymath economist, historian, and political philosopher Rothbard have convinced thousands of scholars to work in his intellectual tradition (natural rights, praxeology, and antistate, antiwar revisionism). At a memorial in ’86, Lew Rockwell told me that “he [Murray] needs his [Robert] Skidelsky,” referring to Keynes’s biographer. Twenty years later, Murray’s mentor and former Gestapo target Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) got his Hülsmann. Murray’s oeuvre will need a team of Hülsmanns (as I learned the hard way).

I looked forward to 70 with only slightly more actuarial confidence than I do to 80. But even “looking forward” distorts my mood; I’m oriented toward the past, the “dead” past that lives in me, the foreign land where they did things differently. Reflecting on my choices, I’m interested, perhaps inordinately, in people who, motivated similarly, made similar decisions, especially the radical New Yorkers. What made them tick? Did any of my moves resemble theirs? In any given year, say, 1936, what was each of them doing? They may have (and often were) oblivious to their contemporaries and their projects, but I am not.

My interest is not restricted to political radicals: there are also theological radicals, like Otis Q. Sellers about whom I’ve written a great deal on this blog and apologetics radicals like Cornelius Van Til and Greg Bahnsen, in whose spirit I wrote Philosophy after Christ. In 1936, Sellers founded the Word of Truth Ministry and Van Til began ministering in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church; Aptheker embarked on his archival research on Nat Turner in Richmond, Virginia (a trip his mother financed). Aptheker was five years Asimov’s senior, but both were alumni of Seth Low Junior College (which closed in 1936) and continued their studies at Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus. Aptheker joined the Communist Party in 1939, but his love affair with cousin (and future wife) Fay rooted him firmly in the Stalinist camp by 1936, by which time he was eagerly consuming every article by Stalinist pundit R. Palme Dutt. Murray was a but lad of 11 attending Birch Wathen School on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

But for an accident of geography, as I noted in a 2019 post, I might have come under the influence, not of Aptheker, but of George Novack (1905-1992), whose interest in history rivaled his focus on philosophy, my specialty. (I invite you to read it, if you haven’t yet.) I’m now immersed in the writings of Alan Wald , a frankly socialist professor of literature for the light he sheds on their presupposed (and unexamined) moral imperative to make “a better world.” I was delighted to read a chapter on Novack in Wald’s 1978 James T. Farrell: The Revolutionary Socialist Years.

Many erudite and sincere romantics and idealists passed through Trotskyism (one of them, Sidney Hook, was my teacher; I, one of his last students), it would have been easy for them to recruit me had the occasion arisen, but by God’s grace, I suppose, it didn’t. Novack was one of the few of that storied generation who “kept the faith” (which he deemed “science”) to his last breath.

I intend no condescension: making sense of Marxism (which is supposed to make sense of the world) is a fool’s errand; once upon a time it was this fool’s. When asked why I didn’t write about my experiences sooner, I say: someone who rationalized Stalinism should be slow to talk about how the world ought to go, or even to confess his rationalization. I’ll let others judge whether my confession is still premature.

That’s more than enough reverie for now. My reaching a “milestone” has been an excuse for the self-indulgence in which your reading has made you complicit. This exercise has lightened memory’s millstone somewhat, but much more grain remains to be ground.